After self-recognition and awareness, but before any real engagement, the phones must open a channel for communication, and commit to exchange data. Humans and other animals do this in a variety of ways using body language and sounds, and it can be as simple as acknowledging the presence of the other party, and recognizing this acknowledgement. As absurd as it might sound, in this case, each phone must be able to let other phones know when they know that they’ve been seen!

In order to accomplish this, we developed a simple method for audio communication between the phones. Even thought this first step consists of a simple language that is made up of only two phrases (“I see you” and “I know that you know that I’m here”), the idea is that it is extendable to include other phrases.

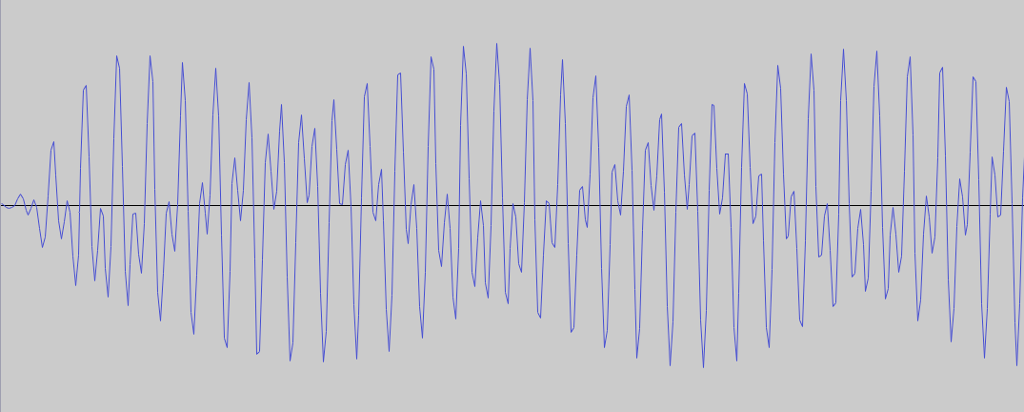

The first attempt was based on DTMF, the same kind of sounds that phones already use to communicate with each other. The idea was to encode a couple of phrases or letters using sounds made up of two pure sinusoidal waves. The following image of a DTMF waveform clearly shows the two frequencies that make up the sound.

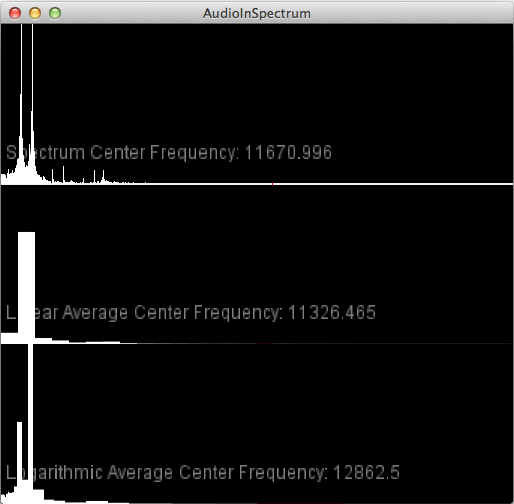

A frequency analysis of this sound clearly shows the two peaks that correspond to the two dominant frequencies being played.

Initial tests seemed promising, but detecting specific tones in the presence of other sounds, including ambient noise, proved to be more challenging.

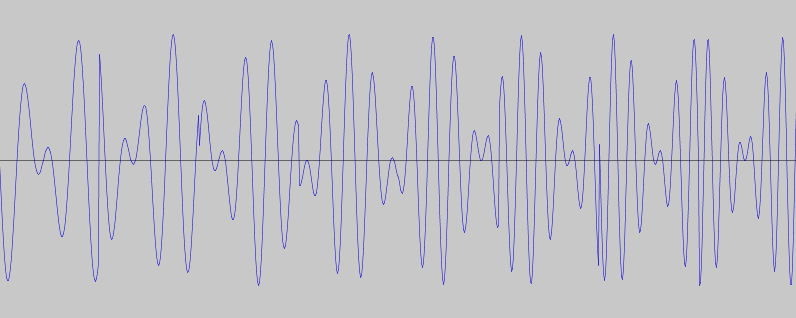

We also tried to detect tone differences instead of specific tones. In this technique, the sound messages are still made up of two sine waves, but unlike DTMF the frequencies of these sine waves are always changing, while their difference is kept the same. For example, a sound could be made up of the following frequency pairs while trying to transmit a tone difference of 500Hz: 1400Hz-1900Hz, 2000Hz-2500Hz, 700Hz-1200Hz, etc.

This was motivated by the intuition that if the tones could skip around the spectrum, maybe they would be less susceptible to ambient noise. The following picture shows the waveform of one of these “skipping frequency-difference” sounds, and in it we can see the points where the two frequencies change.

While these sounds might be less susceptible to ambient noise interference, calculating their specific difference also proved to be challenging. We suspect this has to do with how quickly and accurately the phones can perform the frequency analysis.

So, instead of detecting specific tones or tone differences, we decided to detect quick changes in pitch. This way the specific frequencies are not as important and we can use frequencies that minimize ambient interference. For our particular language made up of two phrases, this means we can get away with simple sequences of rising and falling pitches. For example, a sequence of four rising tones can mean one phrase and a sequence of four falling tones the other. This is what the two phrases look like, and sound like.

We coded a simple Android app to test this communication protocol, using the JTransforms library for doing the frequency analysis.